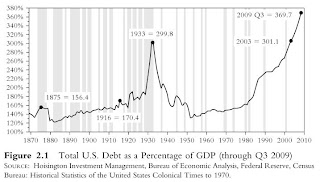

We borrowed like there was no tomorrow. And because we were so convinced that all this debt was safe, we leveraged up, borrowing at first 3 and then 5 and then 10 and then as much as 30 times the actual money we had. And we convinced the regulators that it was a good thing. The longer things remained stable, the more convinced we became they would remain that way. The chart shows how our sandpile ended up. It's not pretty.

"Endgame: The End of the Debt SuperCycle and How It Changes Everything" by John Mauldin and Jonathan Tepper

ReplyDeleteWe are going to start our explorations with excerpts from a very important book by Mark Buchanan called Ubiquity, Why Catastrophes Happen. I HIGHLY recommend it to those of you who, like me, are trying to understand the complexity of the markets. Not directly about investing, although he touches on it, it is about chaos theory, complexity theory, and critical states. It is written in a manner any layman can understand. There are no equations, just easy-to-grasp, well-written stories and analogies.

ReplyDeleteWe all had the fun as kids of going to the beach and playing in the sand. Remember taking your plastic buckets and making sandpiles? Slowly pouring the sand into ever-bigger piles, until one side of the pile started an avalanche?

Imagine, Buchanan says, dropping just one grain of sand after another onto a table. A pile soon develops. Eventually, just one grain starts an avalanche. Most of the time it is a small one, but sometimes it gains momentum and it seems like one whole side of the pile slides down to the bottom.

Well, in 1987 three physicists, named Per Bak, Chao Tang, and Kurt Weisenfeld, began to play the sand pile game in their lab at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York. Now, actually piling up one grain of sand at a time is a slow process, so they wrote a computer program to do it. Not as much fun, but a whole lot faster. Not that they really cared about sand piles. They were more interested in what are called nonequilibrium systems.

They learned some interesting things. What is the typical size of an avalanche? After a huge number of tests with millions of grains of sand, they found out that there is no typical number.

"Some involved a single grain; others, ten, a hundred or a thousand. Still others were pile-wide cataclysms involving millions that brought nearly the whole mountain down. At any time, literally anything, it seemed, might be just about to occur."

It was indeed completely chaotic in its unpredictability. Now, let's read these next paragraphs slowly. They are important, as they create a mental image that helps me understand the organization of the financial markets and the world economy.

"To find out why [such unpredictability] should show up in their sandpile game, Bak and colleagues next played a trick with their computer. Imagine peering down on the pile from above, and coloring it in according to its steepness. Where it is relatively flat and stable, color it green; where steep and, in avalanche terms, 'ready to go,' color it red.

"What do you see? They found that at the outset the pile looked mostly green, but that, as the pile grew, the green became infiltrated with ever more red. With more grains, the scattering of red danger spots grew until a dense skeleton of instability ran through the pile. Here then was a clue to its peculiar behavior: a grain falling on a red spot can, by domino-like action, cause sliding at other nearby red spots. If the red network was sparse, and all trouble spots were well isolated one from the other, then a single grain could have only limited repercussions.

"But when the red spots come to riddle the pile, the consequences of the next grain become fiendishly unpredictable. It might trigger only a few tumblings, or it might instead set off a cataclysmic chain reaction involving millions. The sandpile seemed to have configured itself into a hypersensitive and peculiarly unstable condition in which the next falling grain could trigger a response of any size whatsoever."

Something only a math nerd could love? Scientists refer to this as a critical state. The term critical state can mean the point at which water would go to ice or steam, or the moment that critical mass induces a nuclear reaction, etc. It is the point at which something triggers a change in the basic nature or character of the object or group. Thus, (and very casually for all you physicists) we refer to something being in a critical state (or use the term critical mass) when there is the opportunity for significant change.

ReplyDelete"But to physicists, [the critical state] has always been seen as a kind of theoretical freak and sideshow, a devilishly unstable and unusual condition that arises only under the most exceptional circumstances [in highly controlled experiments]... In the sandpile game, however, a critical state seemed to arise naturally through the mindless sprinkling of grains."

Then they asked themselves, could this phenomenon show up elsewhere? In the earth's crust, triggering earthquakes; in wholesale changes in an ecosystem or a stock market crash? "Could the special organization of the critical state explain why the world at large seems so susceptible to unpredictable upheavals?" Could it help us understand not just earthquakes, but why cartoons in a third-rate paper in Denmark could cause worldwide riots?

Buchanan concludes in his opening chapter:

"There are many subtleties and twists in the story ... but the basic message, roughly speaking, is simple: The peculiar and exceptionally unstable organization of the critical state does indeed seem to be ubiquitous in our world. Researchers in the past few years have found its mathematical fingerprints in the workings of all the upheavals I've mentioned so far [earthquakes, eco-disasters, market crashes], as well as in the spreading of epidemics, the flaring of traffic jams, the patterns by which instructions trickle down from managers to workers in the office, and in many other things.

"At the heart of our story, then, lies the discovery that networks of things of all kinds – atoms, molecules, species, people, and even ideas – have a marked tendency to organize themselves along similar lines. On the basis of this insight, scientists are finally beginning to fathom what lies behind tumultuous events of all sorts, and to see patterns at work where they have never seen them before."

Now, let's think about this for a moment. Going back to the sandpile game, you find that as you double the number of grains of sand involved in an avalanche, the likelihood of an avalanche is 2.14 times as unlikely. We find something similar in earthquakes. In terms of energy, the data indicate that earthquakes simply become four times less likely each time you double the energy they release. Mathematicians refer to this as a "power law," or a special mathematical pattern that stands out in contrast to the overall complexity of the earthquake process.

So what happens in our game? "... after the pile evolves into a critical state, many grains rest just on the verge of tumbling, and these grains link up into ‘fingers of instability' of all possible lengths. While many are short, others slice through the pile from one end to the other. So the chain reaction triggered by a single grain might lead to an avalanche of any size whatsoever, depending on whether that grain fell on a short, intermediate or long finger of instability."

ReplyDeleteNow, we come to a critical point in our discussion of the critical state. Again, read this with the markets in mind:

"In this simplified setting of the sandpile, the power law also points to something else: the surprising conclusion that even the greatest of events have no special or exceptional causes. After all, every avalanche large or small starts out the same way, when a single grain falls and makes the pile just slightly too steep at one point. What makes one avalanche much larger than another has nothing to do with its original cause, and nothing to do with some special situation in the pile just before it starts. Rather, it has to do with the perpetually unstable organization of the critical state, which makes it always possible for the next grain to trigger an avalanche of any size."

Now let's couple this idea with a few other concepts. First, one of the world's greatest economists (who sadly was never honored with a Nobel), Hyman Minsky, points out that stability leads to instability. The longer a given condition or trend persists (and the more comfortable we get with it), the more dramatic the correction will be when the trend fails. The problem with long-term macroeconomic stability is that it tends to produce highly unstable financial arrangements. If we believe that tomorrow and next year will be the same as last week and last year, we are more willing to add debt or postpone savings for current consumption. Thus, says Minsky, the longer the period of stability, the higher the potential risk for even greater instability when market participants must change their behavior.

Relating this to our sandpile, the longer that a critical state builds up in an economy or, in other words, the more fingers of instability that are allowed to develop connections to other fingers of instability, the greater the potential for a serious "avalanche."

And that's exactly what happened in the recent credit crisis. Consumers all through the world's largest economies borrowed money for all sorts of things, because times were good. Home prices would always go up and the stock market was back to its old trick of making 15% a year. And borrowing money was relatively cheap. You could get 2% short-term loans on homes, which seemingly rose in value 15% a year, so why not buy now and sell a few years down the road?

Greed took over. Those risky loans were sold to investors by the tens and hundreds of billions all over the world. And as with all debt sandpiles, the fault lines started to show up. Maybe it was that one loan in Las Vegas that was the critical piece of sand; we don't know, but the avalanche was triggered.

ReplyDelete...[I] was writing about the problems with subprime debt way back in 2005 and 2006. But as the problem actually emerged, respected people like Ben Bernanke (the chairman of the Fed) said that the problem was not all that big, and that the fallout would be "contained." (I bet he wishes he could have that statement back!)

But it wasn't contained. It caused banks to realize that what they thought was AAA credit was actually a total loss. And as banks looked at what was on their books, they wondered about their fellow banks. How bad were they? Who knew? Since no one did, they stopped lending to each other. Credit simply froze. They stopped taking each other's letters of credit, and that hurt world trade. Because banks were losing money, they stopped lending to smaller businesses. Commercial paper dried up. All those "safe" off-balance-sheet funds that banks created were now folding. Everyone sold what they could, not what they wanted to, to cover their debts. It was a true panic. Businesses started laying off people, who in turn stopped spending as much.

...[B]anks may do what unreasonable things when they get into trouble...But the fact is, we need banks. They are like the arteries in our bodies; they keep the blood (money) flowing. And when our arteries get hard, we can be in danger of heart attacks. And it's going to get worse, as banks are going to lose more money on their commercial real estate loans. Commercial real estate is down some 40% around the country.

There are a lot of books that try to pinpoint the cause of our current crisis. And some make for fun reading, like a good mystery novel. You can blame it on the Fed or the bankers or hedge funds or the government or ratings agencies or any number of culprits.

Let me be a little controversial here. The blame game that is now going on is, in many ways, way too simplistic. The world system survived all sorts of crises over the recent decades and bounced back. Why is now so different?

Because we are coming to the end of a 60-year debt supercycle. We borrowed (and not just in the US) like there was no tomorrow. And because we were so convinced that all this debt was safe, we leveraged up, borrowing at first 3 and then 5 and then 10 and then as much as 30 times the actual money we had. And we convinced the regulators that it was a good thing. The longer things remained stable, the more convinced we became they would remain that way. The chart shows how our sandpile ended up. It's not pretty.

I ... always say it is never "different," but in a sense this time is really different from all the other crises we have gone through since the Great Depression... What the very important book by professors Reinhart and Rogoff shows is that every debt crisis always ends this way, with the debt having to be paid down or written off or defaulted upon. That part is never different. One way or another, we reduce the debt. And that is a painful process. It means that the economy grows much slower, if at all, during the process.

ReplyDeleteAnd while the government is trying to make up the difference for consumers who are trying to (or being forced to) reduce their debt, even governments have limits, as the Greeks are finding out.

If it were not for the fact that we are coming to the closing innings of the debt supercycle, we would already be in a robust recovery. But we are not. And sadly, we have a long way to go with this deleveraging process. It will take years.

You can't borrow your way out of a debt crisis, whether you are a family or a nation. And as too many families are finding out today, if you lose your job you can lose your home. What were once very creditworthy people are now filing for bankruptcy and walking away from homes, as all those subprime loans going bad put homes back onto the market, which caused prices to fall, which caused an entire home-construction industry to collapse, which hurt all sorts of ancillary businesses, which caused more people to lose their jobs and give up their homes, and on and on.

It's all connected. We built a very unstable sandpile and it came crashing down and now we have to dig out from the problem. And the problem was too much debt. It will take years, as banks write off home loans and commercial real estate and more, and we get down to a more reasonable level of debt as a country and as a world.

And here's where I have to deliver the bad news. It seems we did not learn the lessons of this crisis very well. First, we have not fixed the problems that made the crisis so severe. We have not regulated credit default swaps, for instance. And European banks are still highly leveraged.

Why is Greece important? Because so much of their debt is on the books of European banks. Hundreds of billions of dollars worth. And just a few years ago this seemed like a good thing. The rating agencies made Greek debt AAA, and banks could use massive leverage (almost 40 times in some European banks) and buy these bonds and make good money in the process.

Except, now that Greek debt is risky. Today, it appears there will be some kind of bailout for Greece. But that is just a band-aid on a very serious wound. The crisis will not go away. It will come back, unless the Greeks willingly go into their own Great Depression by slashing their spending and raising taxes to a level that no one in the US could even contemplate. What is being demanded of them is really bad for them, but they did it to themselves.

But those European banks? When that debt goes bad, and it will, they will react to each other just like they did in 2008. Trust will evaporate. Will taxpayers shoulder the burden? Maybe, maybe not. It will be a huge crisis. There are other countries in Europe, like Spain and Portugal, that are almost as bad as Greece. Great Britain is not too far behind.

ReplyDeleteThe European economy is as large as that of the US. We feel it when they go into recessions, for many of our largest companies make a lot of money in Europe. A crisis will also make the euro go down, which reduces corporate profits and makes it harder for us to sell our products into Europe, not to mention compete with European companies for global trade. And that means we all buy less from China, which means they will buy less of our bonds, and on and on go the connections. And it will all make it much harder to start new companies, which are the source of real growth in jobs.

And then in January of 2011 we are going to have the largest tax increase in US history. The research shows that tax increases have a negative 3-times effect on GDP, or the growth of the economy. As I will show in a letter in a few weeks, I think it is likely that the level of tax increases, when combined with the increase in state and local taxes (or the reductions in spending), will be enough to throw us back into recession, even without problems coming from Europe. (And no, that is not some Republican research conspiracy. The research was done by Christina Romer, who is Obama's chairperson of the Joint Council of Economic Advisors.)

And sadly, that means even higher unemployment. This next time, we won't be able to fight the recession with even greater debt and lower interest rates, as we did this last time. Rates are as low as they can go, and this week the bond market is showing that it does not like the massive borrowing the US is engaged in. It is worried about the possibility of "Greece R Us."

Bond markets require confidence above all else. If Greece defaults, then how far away is Spain or Japan? What makes the US so different, if we do not control our debt? As Reinhart and Rogoff show, when confidence goes, the end is very near. And it always comes faster than anyone expects.

The good news? We will get through this. We pulled through some rough times as a nation in the '70s. No one, in 2020, is going to want to go back to the good old days of 2010, as the amazing innovations in medicine and other technologies will have made life so much better. In 1975 we did not know where the new jobs would come from. It was fairly bleak. But the jobs did come, as they will once again.

So, what's the final message (to our children)? Do what you are doing. Work hard, save, watch your spending, and think about whether your job is the right one if we have another recession. Pay attention to how profitable the company you work for is, and make yourself their most important worker. And know that things will get better. The 2020s are going to be one very cool time, as we shrug off the ending of the debt supercycle and hit the reset button.